Heart words are irregular high frequency words, irregular meaning that their spelling does not match the phonemes we hear or the regular phonics rules of our language. When it comes to heart words and how to teach them, I believe that many kindergarten teachers are struggling with the same conundrums. I’m trying out heart word approaches for the first time this school year. What I do in my classroom and what I write here is based on much reading about cognitive research and how students learn to read and remember words; however, that doesn’t mean that implementation is straightforward and easy. I find myself vacillating from week to week, as discussed below. I write about this topic based on what I know now (November 2021).

Is it really necessary to identify heart words and “hard parts to remember by heart” or can we just have students memorize the words as we’ve done in the past?

In past years, most of us most likely taught high frequency words—whether regular or irregular—by repeatedly showing them to students, both in flashcard style and in repeated language in leveled books. We also solicited parents to help us expose students to words outside of school hours. We all figured the more frequently they saw them, the faster they’d memorize them.

We know better now. We know that students do not memorize words visually. We are learning the science that’s actually been around for many decades—that students process every letter and associate them with each phoneme they hear in words. We know that they must map the letters they see onto the phonemes they hear. A large percentage of students can do this easily and practically on their own. But there’s that other 35 or so percent who need our help. They need us to go over and over the sounds we hear and the letters that we choose to spell those sounds. They need us to talk about which letters make sense and which are going to be hard to deal with because they don’t make sense.

We know the answer is no; no, we cannot just have students visually memorize words like we used to. The main reason is because students weren’t visually memorizing words all those past years. Some were lucky and learning them; others were just guessing or basing their “reading” on clues we gave them, such as the word look having two eyes in the middle.

So, though difficult as it can be at the beginning of kindergarten to talk about the sounds heard in words and the letters used to spell those sounds, we should try to get started.

My experience so far this school year:

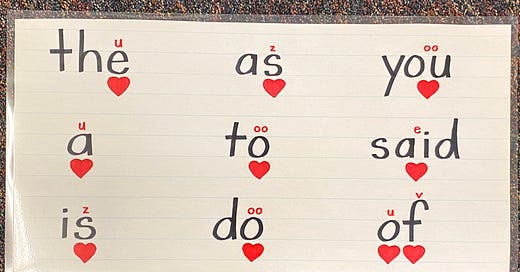

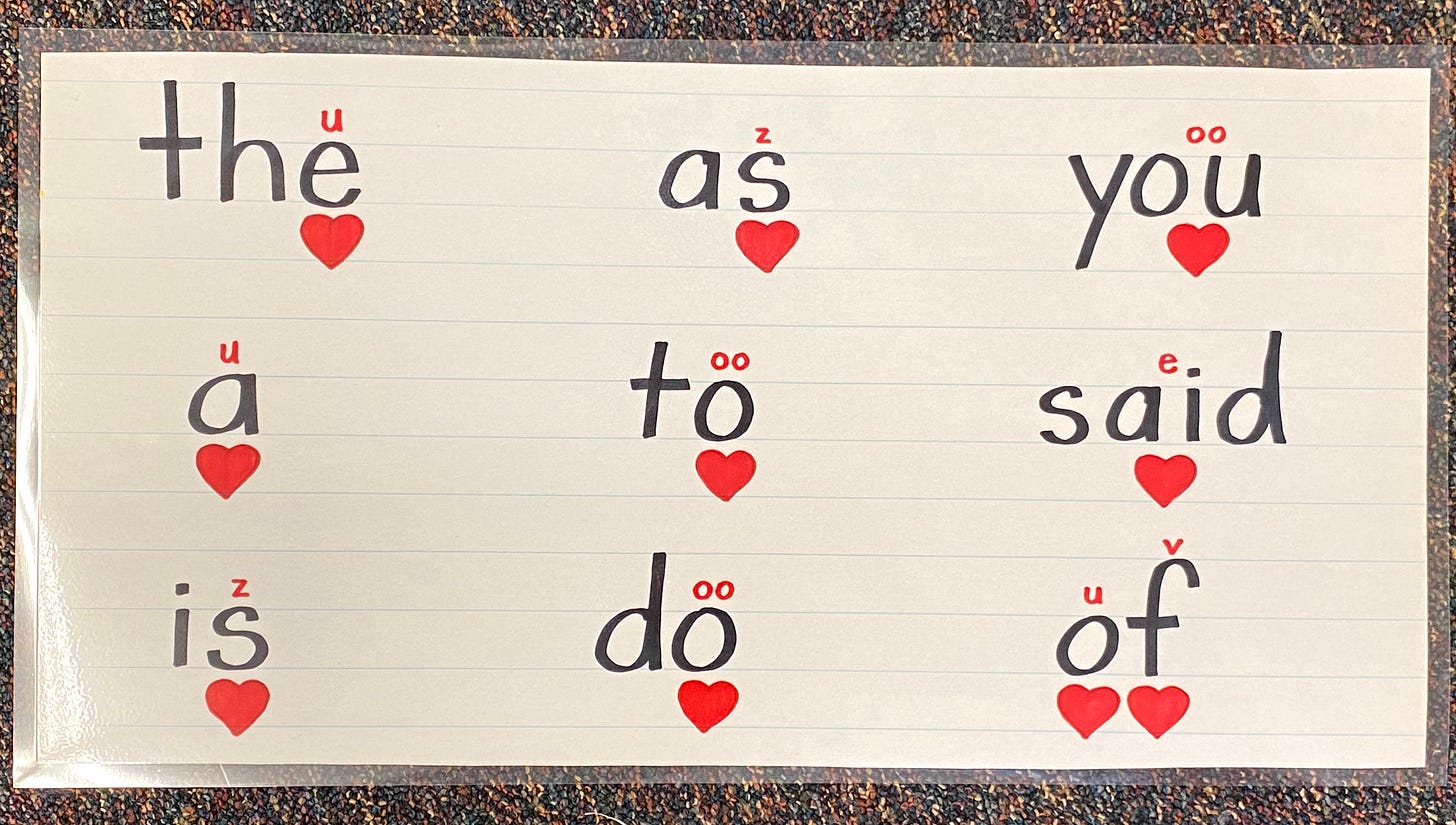

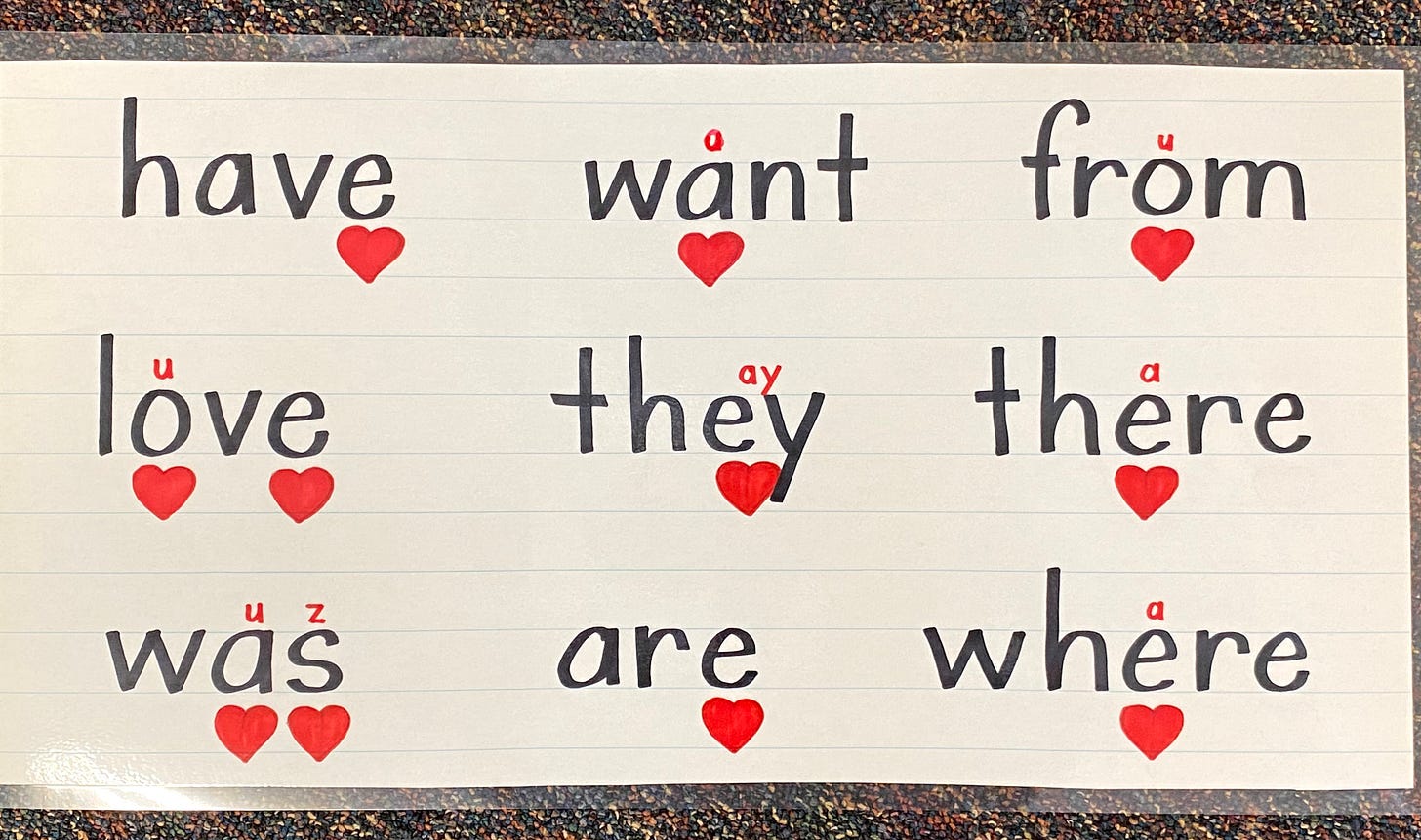

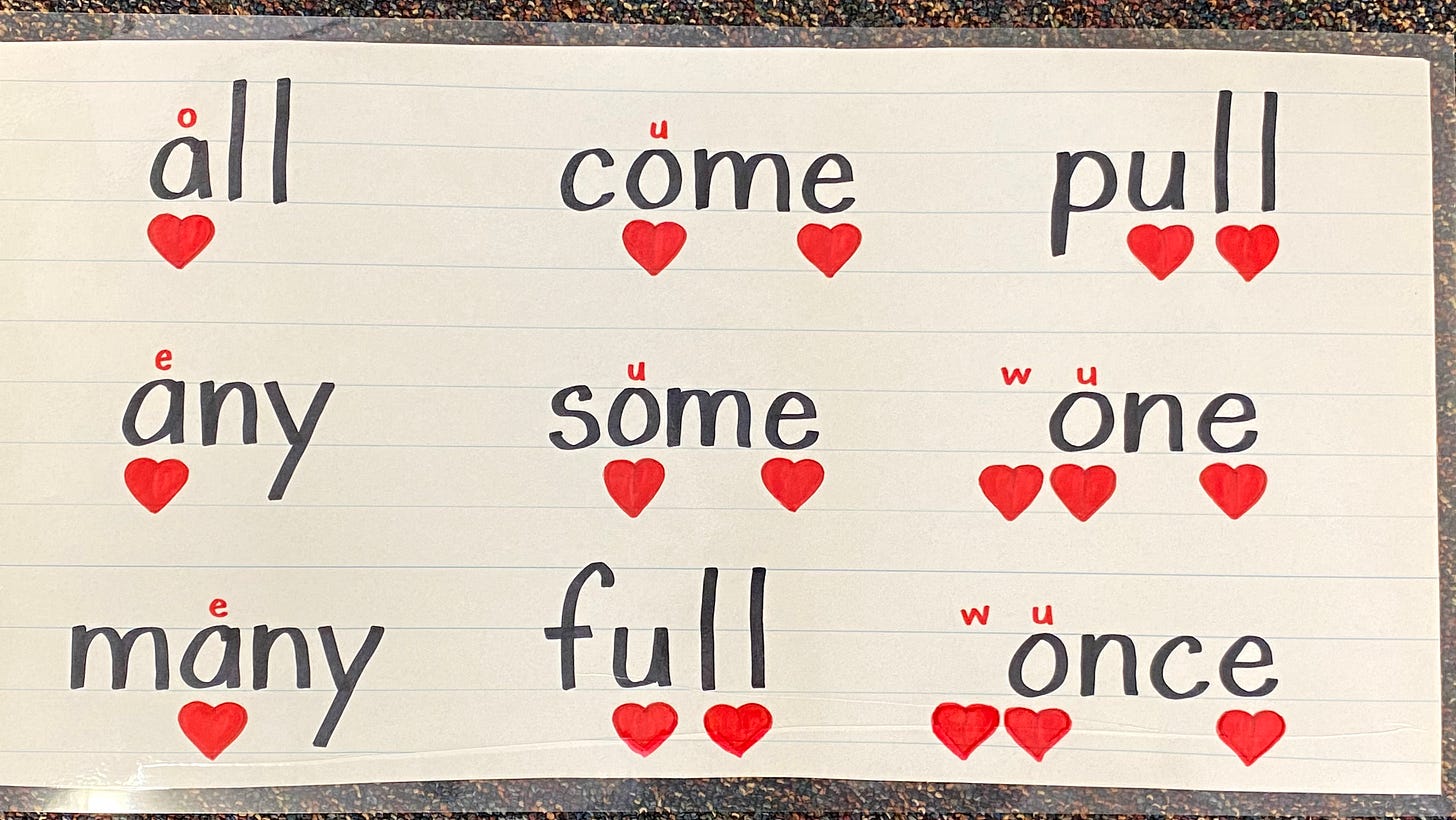

My experience with this actually started last spring when I first learned about heart words and a better approach to teaching high frequency words in general. I separated the irregular high frequency words from the regular ones and made a slide show presentation of the words that supported a routine of 1) seeing the word in print and pronouncing it, 2) segmenting the phonemes in the word, 3) spelling the word, and 4) comparing the graphemes that were used with the sounds heard to determine which were going to be “a hard part to remember by heart”—at which time in the slide presentation a little red heart would magically appear under that grapheme.

Last spring, my students loved this. So did I. This fall, not so much. I’m sure you can guess why. This fall my students do not yet know enough phonics to knowledgeably analyze and discuss words in this way. I do most of the analyzing and talking and they are mostly overwhelmed and bored.

But I press on.

I’ve considered the alternatives, one of which is to just go back to the old way of having them memorize words. Trust me. I’ve considered it about every other day for the past two months. Because the heart word routine is painful at this point in the school year. But I realize the importance of not contradicting myself; I cannot embrace the science of reading and all the work I’ve put into having my students learn letter sounds, phonemic awareness, and the ability and confidence to blend CVC words by November just to go back to encouraging them to look at words as a whole.

The other alternative, of course, is to just not teach them at all. But that’s not an alternative, in my book.

Which words should be introduced and when? How can students practice these words?

One of the main ways we had kindergartners learn to read high frequency words was to use emergent reading leveled texts that used repeated language. If there were seven pages in a row that said She can see the.. we presumed that students would start to learn these words. Most would. But a surprising amount—about 35% of students—cannot learn to read (well) with this approach.

And only a few parents have the knowledge, time, or patience to teach their children to read high frequency words in a way other than memorization. If we aren’t sending words home to be memorized and we’re not using much leveled text, how will students learn the words? How can we have them practice?

Most high frequency words can be decoded and only a few—especially at the kindergarten level—require something other than standard phonics knowledge and blending skills. Thus, any unique practice—other than standard whole and small group instruction that focuses on letter sounds and blending—need only include the few irregular words we identify as necessary for kindergartners to proceed with their ability to read continuous text.

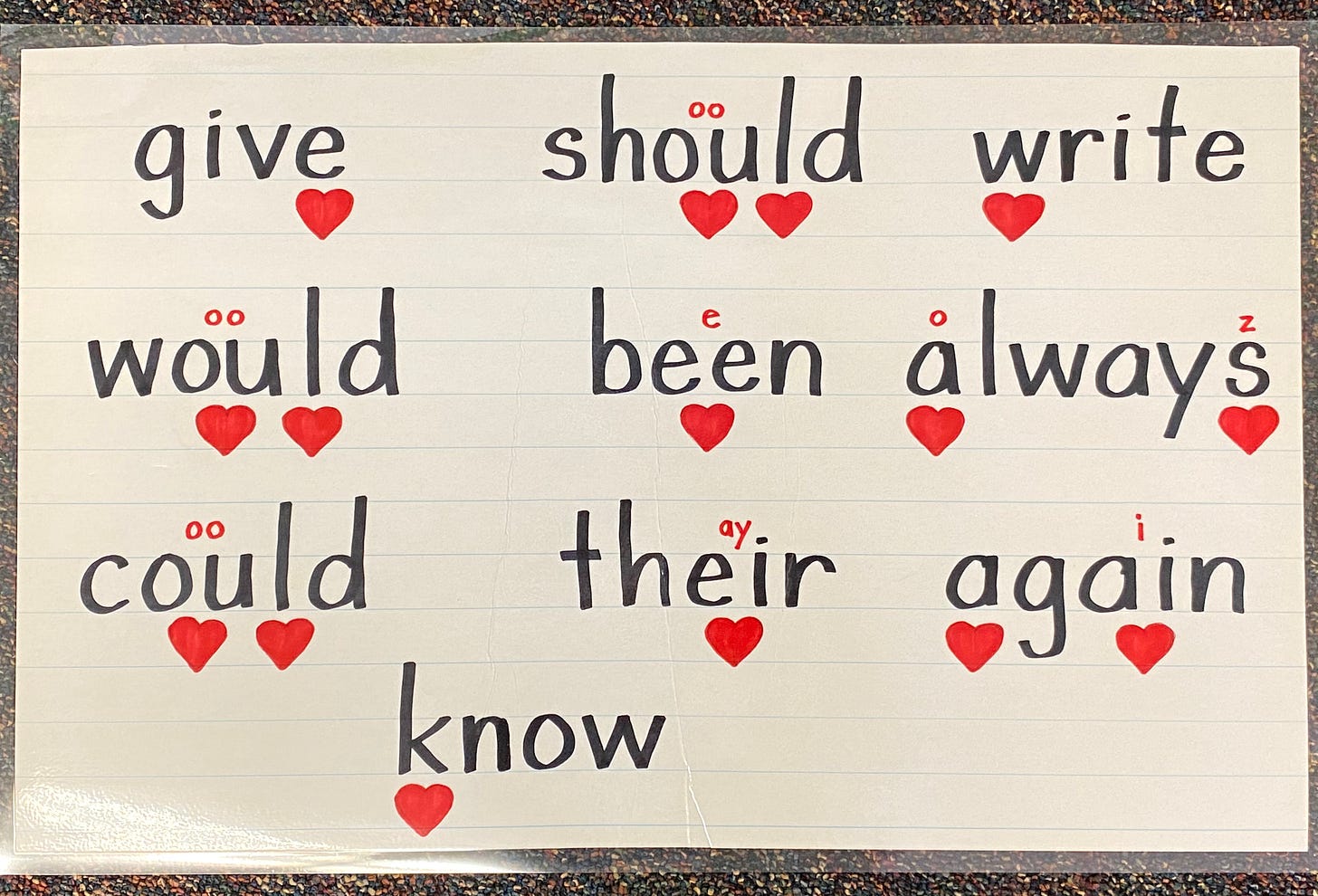

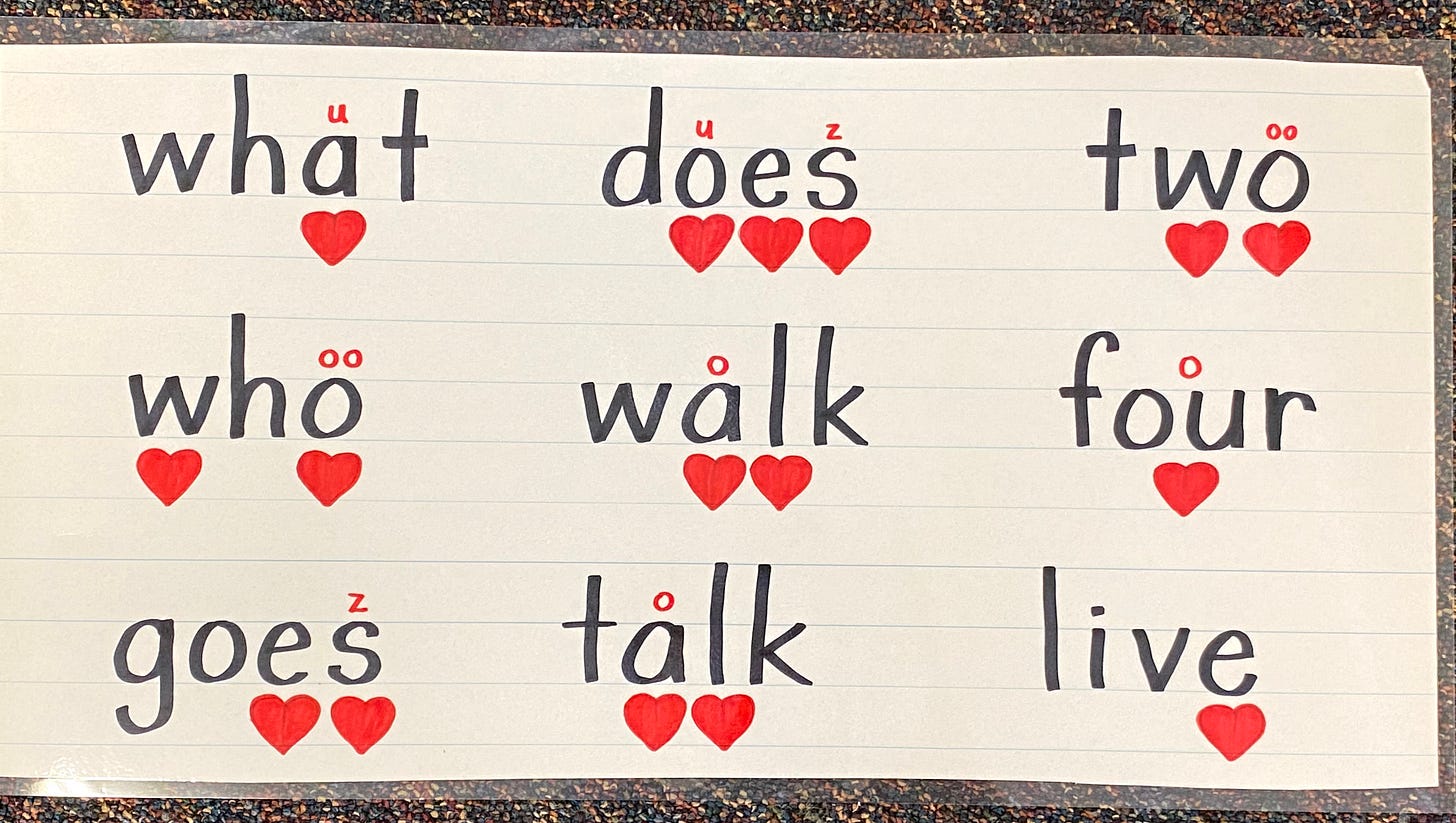

With all the work I did last spring to separate irregular high frequency words from the regular ones and then group the regular words by spelling patterns (into these 34 lists), these are the words I determined to be irregular (based on the phonics that I teach my students; the list might look differently for you) and they are grouped somewhat by difficulty and order in which we would want to teach them.

My experience so far this school year:

For as long as I can remember now, I’ve always taught phonics explicitly and systematically in kindergarten. What I’ve changed up this year is my small group instruction; we’ve gone from—in past years—reading leveled text with such supports as repeating language and picture clues to—this year—working primarily with materials I’ve designed that provide constant support in learning to blend, first two sounds and then three. This huge switch has my students reading (real reading) much earlier in the school year. And this has me agog with how they’ll do with reading decodable passages. I can hardly control myself to not give them decodable passages right now. The problem is that decodable passages have words such as the, a, is, to, has, do, etc. If I want to get decodable passages into the hands of my students and I want them to be successful with them, then I’ll need to teach the heart words we see in them.

So I look for ways to introduce these words and have students practice them, ways that do not encroach on the old-style memorization. So far I am doing this in three ways:

I do our heart word slide show routine once or twice a week for about 15 minutes to slowly introduce new words (one per week) and review the ones already introduced. The purpose of this is to help students analyze the sounds heard with the associated letters/graphemes used, thereby promoting orthographic mapping.

I include the irregular high frequency words I’ve formally introduced in the small group instruction materials I create, the purpose being that students need to practice reading these words in continuous text. So far—November of kindergarten—I am including the words is, the, you, a, was, to, said, has, and do.

About once a week I use a sentence stem during whole group writing time and the sentence stem may include—or lead to the students writing on their own—some of the heart words I’ve taught. On any given day during writing, students are encouraged to refer to our list of heart words for spelling accuracy.

This is what I am doing in November. As students learn more phonics—especially advanced phonics—and our whole group phonics routine changes as the school year goes on, more heart word practice will be incorporated at this time of day. And, as it becomes possible to get decodable passages in front of my students, they will get that all-too-important authentic practice of reading continuous text that includes both regular and irregular words.

What parts of words should we “heart” and should we change that up as the students learn more phonics?

This is a good question and has been asked many times in the articles I read and the forums I follow. The going consensus seems to be that we should only “heart” the truly and permanently irregular parts of words. In other words, we shouldn’t “heart” the i or the silent e on like just because our students have not yet learned long vowels or the effect of a silent e. The only words you should call heart words (in kindergarten anyway; of course there are thousands) are those you see in the pictures above. Any other words you introduce that the students cannot yet decode are not really heart words and should not get hearts anywhere.

My experience so far this school year:

Because of my understanding (to date; it’s always changing as I learn) about what I wrote above, we are accumulating two piles of words in our classroom. The first is the group of heart words we’ve learned; the second is a group of words that come up for various reasons that I intentionally bring the students’ attention to. The latter are words such as like, she, yes, no, or, my, red, little, and some others. If you’re confused by this group of words, you should be. Some are obviously decodable (yes, red); some might be temporarily irregular for my students (my, like, she). Why are they in a group together and how did I choose these to introduce?

These words were introduced at different points in the school year for different reasons, going as far back as early September. For example, my students started learning yes and no (and the concept of word) by spelling their answer during the daily lunch count. Red was introduced when we were reading about the Little Red Hen. Like came up in a sentence stem during writing time. We learned she before I taught sh during whole group phonics. For various reasons, these words had more importance than all the other hundreds of decodable words my students have seen and will see. And that is the only reason they are currently in a group that we occasionally practice. You can tell as time goes on that they will phase out into the gigantic sea of words that students are just capable of reading. Some already have.

What about words that aren’t irregular but fit that category now based on the phonics that students currently know?

When situations arise when students cannot yet be expected to decode a word we’re examining, I say, “I know this part of the word seems weird and it seems like we should put a heart, but it’s actually normal—such-and-such really can make this sound—and I’ll teach you about it some other time.”

Again, the consensus is that only true heart words should get hearts. A word does not go from being irregular to regular once students learn the necessary phonics. It is always either regular or irregular. That being said, you’ll notice some words on my heart word list that might not be considered irregular. Take know, for example. I have a heart under the k, but not one under the ow. What gives? Kn is not irregular once taught. Here is my thinking: I heart the parts of words that I will never teach my students, in other words parts that include phonics that I do not teach in kindergarten. I teach quite a few advanced phonics rules, including that ow can say ou or the long o sound. So I don’t heart that part of the word. But I do not and never have taught kn in kindergarten. It’s just too much, going too far into phonics for kindergarten. I just teach that the k is silent.

How do we talk about and teach the phoneme/grapheme discrepancies found in irregular high frequency words when our nascent readers do not know enough to recognize or understand those discrepancies?

Mostly, be patient and take it slowly. Obviously, students need to know the words the and a fairly early in the school year, especially if you are having your kindergarten students write on a regular basis. But look at some of the other words on the list. Do they need to know them now? Before Winter Break? Not until February? It all depends on what you are doing in your classroom and what you are giving to students and expecting them to read. As mentioned earlier, I am champing at the bit to give my students decodable passages.

I will be patient, however. When I do give them such passages, I want them to have the necessary skills and knowledge of irregular words to be able to read fairly fluently so their comprehension is not compromised and so they feel successful with such text.

And I am taking it slowly. I am introducing one heart word per week. The part of the word that needs to be “hearted” always needs to be explained. I had not yet taught th when I introduced the. But I briefly mentioned that sometimes letters work together and I explained what these two letters make our mouth do (they make us stick our tongue out). After that, we reviewed the word a few times each week, it started appearing (magically!) in the small group instructional materials I create so that students could practice reading it in context, and I began expecting them to spell it correctly during daily writing time.

The best advice I have for talking about and teaching the discrepancies found in heart words is to get started, briefly mention what is happening in the word (even if it’s way over your students’ heads), continue to mention it each time the word is reviewed, and be amazed when your students start to be able to talk about it in the same way you’ve been modeling.

Right in the middle of writing this blog—which I’ve been working on over the course of Thanksgiving Break—I read a blog that posited that a teacher should never teach a heart word until the typical use of the “hearted” part of the word had been taught. In other words, don’t teach the until you’ve taught th; don’t teach said unless your students already know the standard sound of ai. Because of the research she referred to and her thoroughness and my understanding, I once again questioned if I was teaching heart words too early. And I almost decided to not post this blog or the accompanying video. But after much thought, it only served to solidify my philosophy and mission. I am embracing the science of reading but only to the point that it is practical. Our goal is to teach students to read and to get them to love reading. I will share ideas and materials that facilitate this, not hamper it. In my opinion, it is okay to slowly introduce and teach heart words and it is not okay to think we can control every aspect of what students encounter and learn. If we are teaching students to read—which we should be—then we cannot expect them to not see the word said and figure it out on their own. We may as well facilitate and enhance how they are going to learn and map this word.

My experience so far this school year:

I was just about to give up on this whole heart word teaching process when, one week not long ago, my students were able to answer my questions and started demonstrating that they understood what was happening in words.

I knew at that point that what I had been doing—though I was unsure and it didn’t feel right—was working. I could sense that students were starting to orthographically map these difficult irregular words and that they were becoming a permanent part of their sight word vocabulary and list of words they could spell.

For now, I will continue on with this teaching process. I’ll keep you posted on whether I determine it to be highly effective or if I rethink it for this year or for next.

In the video, you’ll see The Name Game in action in our classroom. Using the daily name game is how I introduced my students to the concept of hearts. Before learning some heart words, they understood what the heart meant and this was tremendously helpful.

You’ll also see my use of the heart word slide show (click on the link to access and edit as you wish). It’s not a fast-paced, fun activity, for all the reasons talked about above. It is a way to facilitate the discussion needed for students to internalize (orthographically map) the more difficult-to-learn irregular high frequency words. As stated above, the use of the heart word slide show is based on my current best understanding of how and why to teach these words in kindergarten.

I hope it is helpful. If it is, you might want to consider getting posts like this on a regular basis by subscribing to the paid version of Busy Bee Kindergarten. With that subscription, you will also have access to all my small group instructional materials and 100+ past posts and videos.

Me too! I was feeling unsure of how I was teaching the heart words. I so appreciate you walking us through your thought process. I also really appreciate the video on the Heart Word Slideshow. I need to slow down and spend more time like you do with it! Thank you for all you do!!!

Oh wow! I really needed to read this right now! I was having the exact same feelings about Heart words and wondering if I should continue teaching them! Hearing this has affirmed that I need to continue and has given me some clarity. Thank you so much for sharing your thinking about this!!